Rick Burkhardt, Lisa Clair, Jessica Jelliffe, Jason Craig (Evgenia Eliseeva)

The A.R.T’s most recent hip New York import is , now running at Oberon. The show opens with three speakers talking in a kind of broken academic cant in something that’s part book talk and part lecture. Their takes on the book are humorously weighed down by their personalities. This is reader response criticism at its highest.

One has a kind of manly fascination with Beowulf, another has an erotic fascination with the titular character, and the third is a classic feminist. It’s this third reading that the show predictably relies the most on. That take is probably fine if you never had to read Beowulf for school or if you’re a feminist who prefers the standard lines of discourse, but I find it kind of boring, reductive, and dismissive–kind of like going around saying is gay, and why, and leaving it at that.

Rick Burkhardt, Lisa Clair, Jessica Jelliffe, Jason Craig (Evgenia Eliseeva)

I was hoping the show might put a little more spin on things and take us beyond the conflict between the matriarchal and the patriarchal, especially since the plot isn’t all that interesting by itself if you know it. Perhaps what’s most interesting about Beowulf is its canonization–but this is taken for granted here. I’ll be fair and say that they do take on Beowulf in old age, but with jokes about how they almost skipped over it after things are wrapped up with Grendel’s mom. I think pulling from the latter part of the book, drawing Beowulf as a kind of aging rock star would have been more interesting than a typical assault on his violent machismo.

While I didn’t keel over laughing at Jason Craig (as Beowulf) gesture at his codpiece, there were some good lines of anachronistic dialog between Beowulf and Grendel (Rick Burkhardt). And Jessica Jelliffe (as Grendel’s Mom) had a cool cabaret vibe going. Much of the show had the qualities of a radio play and I might’ve had more of a soft spot for it had it been on the radio.

Props to the band, which includes a great clarinet player (Mario Maggio), a guitarist who was amazing with a slide and array of effect pedals (Sam Kulik), and a couple trombones that kick out some brass band bass. Multi-instrumentalist Brian McCorkle, who sang a few verses as King Hrothgar, had the most natural stage presence of the troupe. But behind the musicians and ridiculousness, there wasn’t enough of an interesting spin on the text for me.

]]> http://www.bostonlowbrow.com/2013/05/beowulf-art-oberon-review/feed/ 48I don’t think there’s a company in town that’s better equipped to take on Thornton Wilder’s early short plays than . Dealing with their brevity and vast range, while maintaining their headiness and sense of comedy isn’t easy to do. These plays jump from the mythological to the spiritual to the philosophical with slapstick and history and music. Keeping all this afloat goes far beyond what’s necessary with any conventional text. But, at the end of the day, you’re left with some very difficult texts written by a budding intellectual–and we all know how hard young intellectual artists like to make their audiences work.

So I can’t say I walked out of Director Matthew Woods’ production feeling as positive about it as I have after his other recent shows. He pulled several of his old aesthetic tricks out of his bag–actors winding string around each other in melancholy choreography and manipulating handheld puppets–but I missed the usual experiential cohesion I get from Imaginary Beasts. With music, lighting, and wonderfully choreographed movement Woods is usually able to construct what feel like eery dreams, but there’s a distinct lack of that experience here.

And maybe that’s just what happens when you put on nine short plays that skip around in subject matter from Mozart to a dying Carolingian soldier. Imaginary Beasts is perfectly able to support the intellectual content of these texts and elevate it with their usual heavily stylized style. The talented and witty company has a few much appreciated additions of dancers and vocalists that provide some great little nuggets of musical performance–combined with Woods’ own classical music soundboard DJing. But this chain of scenes, characters, and experiments in dramatic conventions is dampened by its difficulty and academic significance.

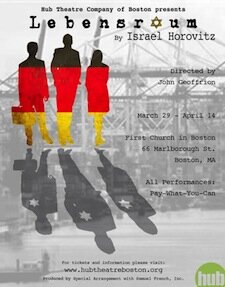

]]> http://www.bostonlowbrow.com/2013/04/imaginary-beasts-takes-on-thornton-wilders-early-stuff/feed/ 63 I usually don’t get that excited about new groups appearing on the Boston fringe scene. There’s a part of me that fears too many people (or egos) trying to do their own thing only strains a finite number a resources and pits companies against each other for what is a limited audience. But I walked out of production of Lebensraum extraordinarily happy to have encountered this new group.

I usually don’t get that excited about new groups appearing on the Boston fringe scene. There’s a part of me that fears too many people (or egos) trying to do their own thing only strains a finite number a resources and pits companies against each other for what is a limited audience. But I walked out of production of Lebensraum extraordinarily happy to have encountered this new group.

Now, even with their pay-what-you-can ticket policy and non-traditional digs at Boston’s First Church, I wouldn’t say they’re breaking the mold. Unconventional spaces can be uncomfortable and, when it comes to the “financial barriers” to theater, I’m much happier to just pay than have the arm put on me. (I do pay for tickets often and put my money where my mouth is as much as I can.) On top of that, I think there’s a danger to fringe companies competing towards a zero dollar ticket, when they are putting on good work that’s never free to produce. Anyways, if there’s one financial hindrance in Boston to getting people into shows, it’s probably the BCA box office fee.

What Hub Theatre does have going for itself is a technical savviness that’s too often missing from Boston’s smaller shows. Their Lebensraum was tight and captivating. Of course, the Israel Horovitz’s play is well structured and laden with all sorts of cleverness, but Director John Geoffrion’s production shook out every fragment of satire, comedy, and drama. He and his cast of three kept a pace that would put them in the lead in the Marathon on Monday, never falling into awkward, poorly constructed or redundant sequences. It’s solid structure that makes good, accessible art great; from Middlemarch to episodes of Cheers. Lebensraum has that and, more importantly, Geoffrion gets it.

Horovitz’s plot relishes its details, but in short it imagines a future where a German Chancellor makes a public call to the world for six million Jews to “come home” to Germany. Controversy ensues. German workers fear for their jobs (and daughters). Israeli militants plan an infiltration, believing this international “apology” is only a ruse to begin a second holocaust. Beginning with journalistic narration’s of neo-nazi’s being trampled and rabis being strangled, Horovitz provides a wonderfully descriptive chain of events involving dozens of characters. Slowly, he shifts from these mock-journalistic vignettes as the main characters are teased out, and suddenly, it doesn’t really matter that everything is made up. Bigger issues like retribution, corruption, love, and hope come to bear. While this fictional future revolves around intentionally absurd imagined events, that very real past is explored through well crafted personal stories.

Actors Jamie Carrillo, Lauren Elias, and Kevin Paquette wear a lot of different hats. I’m being literal here. The set isn’t much more than a couple coat racks strewn with arm fulls of prop-costumes to let them shift in and out of Horovitz’s dozens of interconnected characters. Carrillo and Elias are excellent as they become the Romeo & Juliet of this new Germany and Horovitz begins to warp not just politics, but dramatic cliches as the play culminates in a series of very clever contrivances.

I’m looking forward to more from Hub Theatre, particularly a show about Anne Hutchinson in the fall called Goodly Creatures.

]]> http://www.bostonlowbrow.com/2013/04/hub-theaters-lebensraum/feed/ 196A Raisin in the Sun takes on a complex subject matter that’s not easy to discuss, unless you lace your discussion of it with generic, PC statements on race and oppression. I think this is why so much focus is put on the segregation issue that comes up late in the play, when our protagonists, the Younger family, are asked not to move into the house they bought in an all-white Chicago neighborhood. While there’s some historical importance here (most interestingly, how they were priced out of the black neighborhoods), it’s a minor point to the play.

It’s Walter’s–I’m not sure what to call it–that the play rests on. His neurosis, pain, hubris, anger, weakness, and/or discontent. Everything else is tangential to this; the optimistic lecture on the slow progress of change delivered by Joseph Asagai, the African student; the quick dip into residential segregation; and the jokes at the expense of the Black nationalism movement. The segregation issue only comes up to push Walter past morality and sanity, where he’s willing to swallow racism and prejudice for money. And money is not just money here. He’s trying to recoup his father’s life insurance payout…which he lost…by handing it over to a buddy, in cash, so that he could bribe people for a liquor store license…including the portion his mother set aside for his sister’s tuition but gave to him so he would feel more like a man.

Playwright Lorraine Hansberry lets Walter be her hero in the end, but I think that’s just to give the show a happy ending. Pieces of the play do have a sitcom quality. What makes the play worthwhile is the fact that it’s not easy to align oneself with Walter. He lacks the nobility our fiction likes to endow onto the oppressed. He’s both our villain and our protagonist. And his problems are as complex as our relationship to him. And that’s why the character is so powerful, especially in the hands of LeRoy McClain, whose performance at the Huntington is vastly superior to Sidney Poitier’s in the 1961 film (and certainly better than ). McClain sustains so much emotional intensity, one would think he’d pass out during the curtain call.

Corey Allen, LeRoy McClain (Walter), Corey Janvier (Travis) (T. Charles Erickson)

I think Walter’s anger is of the time of the play’s 1930s setting, but it comes off as being highly relevant. While Walter’s a cynic, it’s not difficult to make the connection between him and the 99%/Occupy movements. Or just that violent lake of magma beneath America’s seemingly sedimentary surface at any given time in the 20th century. This is the real history of racism and greed and economic and social opression in America, where it’s victims are not noble, deserving martyrs, but weak humans.

Clint Ramos has put together one of those massive, rotating sets that are becoming a mannerism of the Huntington and Walter’s anger is mirrored by blaring free jazz interludes. The production opens with a shout out to Chicago geography–a hip hop track with lots of references to streets and corners. Director Liesl Tommy has smartly undercut Walter’s intensity with comic relief from Walter’s sister Beneatha (Keona Welch). Her girlish promise, wisecracks, and back & forth with two suitors provide an endearing foil to Walter’s sad, fated desperation. The character of Ruth (Ashley Younger), Walter’s wife, takes a back seat here. It could be enhanced, but she’s not fully fleshed out in the text to begin with. She’s so forgiving of Walter and almost awkwardly silent at some of the play’s tensest moments that we wonder who she really is.

]]> http://www.bostonlowbrow.com/2013/03/raisin-in-the-sun-huntington/feed/ 37I don’t expect every show I see to knock me over. The best playwrights, actors, and other theater creatives all have duds. And that’s OK. There’s often a great play, or a great performance, or some cool lighting effects there to put a positive spin on any kind of overall weakness or mediocrity, especially in cases where you’re watching a fringe group develop over several seasons. But, to put it bluntly, I can’t stand plays or productions that are too damn long.

And I like long things. I think other people do to. Even though some might argue that our culture is moving from films to video clips, or from albums to mp3s, there are other shifts that point to the opposite. On demand cable and Netflix subscriptions let people consume television at marathon rates. And they often do, watching The Wire, Lost, or Breaking Bad for hours, if not days at a time. Many modern TV shows are, in part, designed to be consumed this way and post-air ratings are now a big part of the numbers that decide whether shows are renewed.

My point is that there’s nothing wrong with long things and that I don’t think 3 hour performances have become obsolete in this age of YouTube and Tweets, but an audience member’s time has to be earned. A 2-3 hour duration should be considered by a playwright or a director (who might be choosing a long work to produce, drawing a play out with musical interludes, or abridging the text) as a narrative tool, not a cultural standard. After all, had a few of history’s great playwrights decided to write differently, the average duration of play might well be 15 minutes long, or 6 hours.

Now, larger houses with subscriber bases and, for Boston, high ticket prices have something of a self-imposed obligation to put on a shows that are at least 2 hours long. If they come in under that, people would complain about not getting their money’s worth, or something like that. And that’s not entirely unreasonable, if they made the drive in from Weston and everything.

The frank truth is that it’s easier for a big budget production to grip even the most enuretic audiences. It’s a much greater challenge for a small theater group, without a massive revolving set, well known actors, and a modern HVAC system. But, possibly in compensation for that, they have the freedom to do almost anything they please. I’d love to see more short plays from the fringe scene. Some of the best nights of theater I’ve had in Boston have been double bills of short plays and I’d much rather climb aboard the 1 bus after a night of taut theater than a show that had me looking at my watch, even if it means an early night.

But, I often see an unwillingness either to produce shorter texts or to cut plays to a length where they would have become much more nimble for performers, directors, and audiences. While a full text Hamlet is powerful, you can cut a lot from it and still do something great without trying your audience.

And this brings me to the most difficult part of this post; the production that led me to write it. BCAP, the “professional extension” of BU’s theater program, is currently running . The show has some strong acting and cool lighting effects, but comes off as if it’s being performed for some kind of academic posterity. This once controversial text by South African playwright Athol Fugard dates back to the sixties and is modern in the 1960s sense of the word. But at 2 1/2 hours, one questions the relevance of this weighty two man meditation race.

This is not to say that social relevancy is a requirement for good theater. I’m all for abstract meta irrelevancy. But this play was written, produced, and subsequently revived in order to be socially relevant–in the sixties and eighties when it was. Time’s erosion of Blood Knot‘s political bedrock, as well as the estrangement of its political message from its homeland, and that message’s packaging in a semi-experimental 1960s script, makes the production come off academic. And, I think, at least here and now, it’s demanding of audiences without offering them much in return.

Cut it down, and I think you’d have something more alive, more interesting, and there less for its own sake. Blood Knot‘s central metaphors don’t require nearly as much development as Fugard gave them and the play, whether you see it as being relevant today or as a piece of the cultural record, would be much stronger in a dose 60-70% of its current size at BCAP.

]]> http://www.bostonlowbrow.com/2013/02/on-duration/feed/ 51All the pieces are in place to send the ART’s production of The Glass Menagerie to Broadway. And I mean the Broadway that still kinda matters, not the tourist traps state officials would bribe producers to have Boston become a proving ground for. There’s the gushing review from Ben Brantley, there are actors with New York and film & television credits, we have classic text just oh-so-rightly modernized, and there’s a very cinematic aesthetic element to the show–long musical interludes and things like that.

The despondence and stark realism of Williams is all there too, but director John Tiffany and set designer Bob Crowley have set the play in a surreal space, accentuating the play’s actual setting. Not in some low rent quarter of St. Louis, but deep down in the memory of our narrator/sometimes protagonist Tom. An M.C. Escher like fire escape steps upwards, making this broken family’s shabby apartment feel like its underground. In the play’s present, it’s Tom’s dungeon. And years into the future, long after he has climbed out and apparently “lived” in the world, following in the footsteps of his wayward father, Tom narrates his memories of this place as if it’s a little prison in his soul. And it looks like it. The dimly-lit set is something out of one of those movies where they go inside people’s dreams.

As Tom, Zachary Quinto is something of an incarnation of Tennessee Williams. He’s sly, poetic, and a little effeminate. As both character and narrator, his projection and commandment of the stage is extraordinary. He shifts about, like a calmly neurotic fish out of water conveying both frailty and a supreme intelligence.

The reviews I’ve read have flatteringly called Cherry Jones’ portrayal of Amanda straight. That is to say, not some grotesque parody of a beaten down Southern belle. Perhaps it’s Williams’ text seeping through, but there’s just so much madness to her machinations to marry off her daughter. She’s perfectly reasonable, somewhat loving, and often competent, but beneath every maternal act and smooth sales pitch for whatever lady’s magazine she hocks over the phone, lurks a woman sick with delusions. In many ways, she’s sicker than her daughter Laura.

Williams’ great dramatic coincidence is well played here; the Gentleman Caller (Brian J. Smith) that happens to be Laura’s high school crush. It’s painful to watch Smith and Kennan-Bolger (as Laura) build there chemistry together, as this high school hero lately humbled by warehouse work, breaks down Laura’s handicapping shyness with gentle advances. But as good as things seem to be going for Laura (and by extension, the rest of her family), we spend this whole portion of the play just knowing that everything is spiraling towards the same starkness the play began with. Yea, it’s a downer. But the cast and crew have sketched a powerful emotional arc into this visually unique production that I don’t think anyone’s going to want to miss. So go ahead and get one-up on those New Yorkers while you can.

]]> http://www.bostonlowbrow.com/2013/02/the-glass-menagerie-ar/feed/ 66

There’s been a lot of chatter on how David Cromer’s production of at the Huntington is somehow hard–a vacuum of the nostalgic hokeyness typically painted over Thornton Wilder’s text by high school drama teachers. And perhaps that’s true. If we get an extra coat of anything here, it’s irony and acerbity and metaness, mostly delivered by Cromer himself who’s come to town as a kind of traveling theatrical maestro, casting a whole slew of local actors for this local installation of his successful New York production. (It’s sort of a traveling one man show with a cast of at least twenty.) But Cromer didn’t arrive without a suitcase full of rural New Hampshire charm. All the warmth that, certainly more so than its modernist devices, has made Our Town the great American play is still there, tugging at heart strings and sucking water out through tear ducts. Even through the delightful and somewhat notorious third act, the play maintains a warm sense of humor that always seems to be there in the nick of time to cut through any melodrama. All in all, I’d call it funny and a little bit sad. Even death, at least for a few moments, is a happy place of calmness, comfort, and reunion.

Cromer puts his actors in what are probably their own contemporary clothes, turns the house lights up all the way, and doesn’t do more in terms of props and scenery than borrowing a couple spindle-backed chairs from the Huntington’s prop room. But, while Emily may not have a moon to look up at, the production isn’t completely spare of elements to enhance Wilder’s carefully articulated moments. During some of the play’s more poignant scenes, Hymns waft down from a BCA catwalk, where Grover’s Corners’ Schubertian choir director sits at a piano directing his small chorus. As drunk as he might be, they don’t sound too bad. Even behind Cromer’s extra layer of irony, all those practical declarations of love, small town details, and peeks into a future no happier and no sadder than Grover’s Corners’ present still spin the deepest emotion and drama out of the humble.

Cromer’s signature touch is a surprise dénouement that breaks down the pillars of Wilder’s temple to theatrical illusion. I usually don’t worry about dropping spoilers, but I really don’t want to ruin this one because it’s not just a plot twist. It’s a brilliant and perfectly executed artistic twist that disrupts our experience and enhances Emily’s metaphysical walk back into the world of the living, and into Wilder’s thesis on small town life (or life in general) that I can’t phrase all that well. All I can say is that I’d argue that Wilder was being a little darker than someone else’s description of him being warm and nostalgic. And that I’d also argue that he was being a little warmer than someone else’s cold and cynical description of Our Town‘s thesis.

]]> http://www.bostonlowbrow.com/2012/12/huntington-our-town-boston-review/feed/ 18